Stem cell editing, complete genome, and cane toad resistance mark necessary steps.

Colossal, the company founded to try to restore the mammoth to the Arctic tundra, has also decided to tackle a number of other species that have gone extinct relatively recently: the dodo and the thylacine. Because of significant differences in biology, not the least of which is the generation time of Proboscideans, these other efforts may reach many critical milestones well in advance of the work on mammoths.

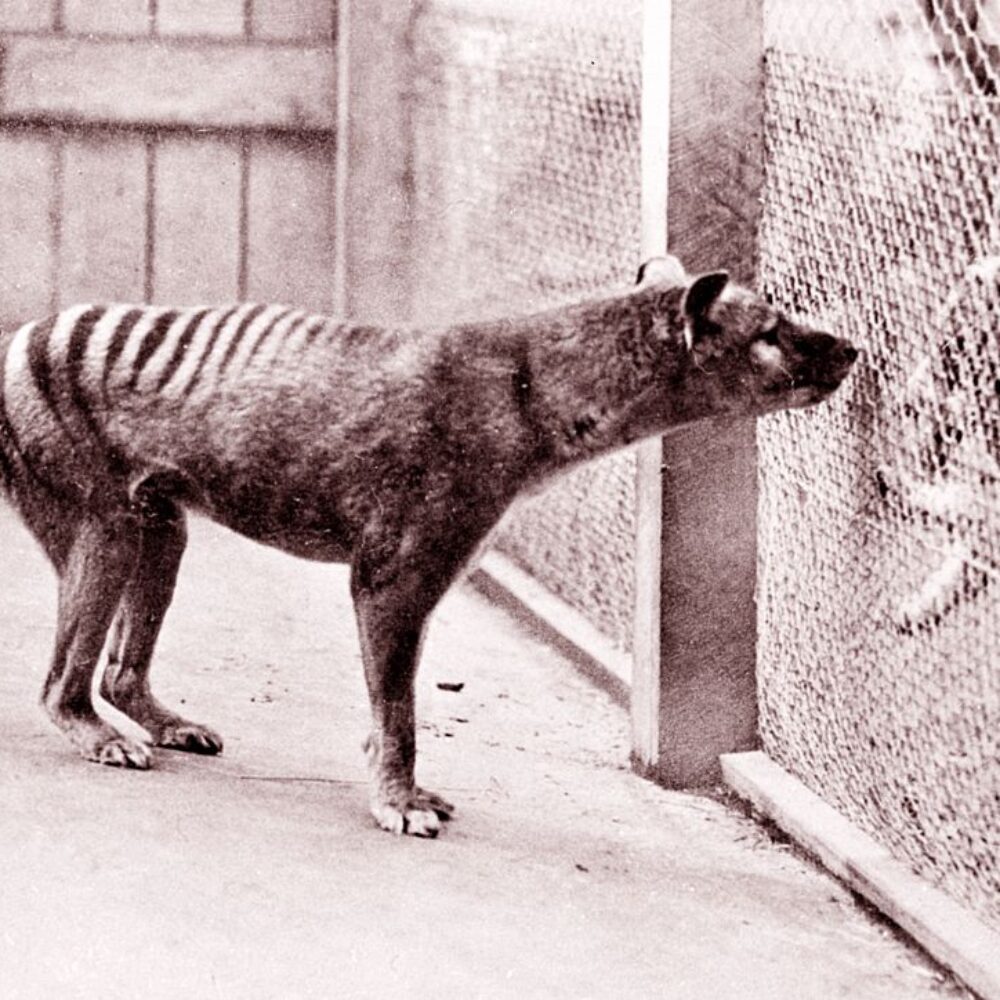

Late last week, Colossal released a progress report on the work involved in resurrecting the thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger, which went extinct when the last known survivor died in a zoo in 1936. Marsupial biology has some features that may make de-extinction somewhat easier, but we have far less sophisticated ways of manipulating it compared to the technology we've developed for working with the stem cells and reproduction of placental mammals. But, based on these new announcements, the technology available for working with marsupials is expanding rapidly.

Cane toad resistance

Colossal has branched out from its original de-extinction mission to include efforts to keep species from ever needing its services. In the case of marsupial predators, the de-extinction effort is incorporating work that will benefit existing marsupial predators: generating resistance to the toxins found on the cane toad, an invasive species that has spread widely across Australia.

The primary threat from cane toads comes from bufotoxins, a group of related, complicated chemicals that bind to a protein found on the surface of cells called ATP1A1, which helps control the traffic of ions across the cell membrane. Andrew Pask, who is leading Colossal's marsupial efforts, told Ars that animals in the cane toad's native range in Africa share a mutation in ATP1A1 that greatly reduces bufotoxin binding. Now, the team has engineered that change into the genome of a marsupial stem cell line and showed that it boosted resistance by a factor of over 6,000. (A manuscript describing some of this work is available.)

For the de-extinction process, the goal would be to ensure that the thylacine could survive in the presence of the cane toad. But Colossal has branched out into a conservation effort, called the Colossal foundation, that aims to keep threatened species from needing its services in the future. As part of that effort, the research team has generated stem cell lines from a surviving Australian carnivore, the quoll, which has become officially endangered largely due to cane toad ingestion. The goal is to ultimately engineer can toad resistance into the quoll stem cells and get the gene circulating with the wild population, allowing them to survive contact with their invasive neighbors.

Key changes

Meanwhile, that edit and more has been going on in stem cells derived from the fat-tailed dunnart, the closest living relative of the thylacine. Pask's team is announcing that they've made over 300 distinct edits in its genome. Ben Lamm, Colossal's CEO, told Ars that they've worked out ways of doing more edits at once without off-target effects (where editing occurs in the wrong location) and have been doing multiple rounds of editing in a single cell line.

What those edits are has been the product of several efforts. To begin with, Colossal has obtained a nearly complete genome sequence from a thylacine sample that was preserved in ethanol a bit over a century ago. According to Pask, this sample contains both the short fragments typical of older DNA samples (typically just a few hundred base pairs long), but also some DNA molecules that were above 10,000 bases long. This allowed them to do both short- and long-read sequencing, leaving them with just 45 gaps in the total genome sequence, which the team expects to close shortly.

This is exceptionally complete for an extinct species and can help provide a greater degree of confidence that the team has identified all the DNA differences between the thylacine and its closest living relatives.

The same sample also provided something that's almost impossible to get from extinct species: messenger RNA molecules, the products of active genes. By analyzing these molecules in specific tissues (the sample was limited to the animal's head), we can get a picture of what genes were active in the adult animal. "By looking in the adult tissues it can inform us about the expression of olfactory receptors and its sense of smell, taste receptors and its sense of taste, eye gene expression can inform us about its vision spectrum, and brain samples can inform us about brain function," Pask said.

The team has also identified a set of genes that may be involved in craniofacial development by reasoning that the similarity between a thylacine's head and that of a wolf might be due to some similar genetic changes. So they looked for regions where dogs, wolves, and thylacines have picked up a large number of changes, suggesting that evolution may be selecting for something new. They've identified multiple “Thylacine Wolf Accelerated Regions” or TWARs, which were all segments of DNA that controlled the activity of nearby genes.

They started by confirming that these could drive gene activity in bone cells. They then chose three TWARs from the thylacine genome and swapped them into the equivalent locations in the mouse genome. They did cause differences in craniofacial development, despite the roughly 150 million years separating the different lineages. Unfortunately, the details of this work haven't been published yet.

Ex utero?

The final thing the company announced was that it was working on getting dunnart embryos to develop outside of the womb. Marsupials are born at a point that's roughly only halfway through normal mouse development—all the organs are in place, but haven't matured—and finish developing in their mother's pouch. Rather than working with surrogate dunnart parents for a much larger thylacine, Pask's team is considering trying to get them to develop to birth in an artificial uterus. And they say they're making progress, getting dunnart embryos to get about two-thirds of the way through a normal pregnancy.

At this point, they've got immature neural cells and have started forming the cells that will go on to form muscles and the vertebrae. But many critical events need to happen in the remaining one-third of the pregnancy, and Colossal isn't ready to talk about what goes wrong to stop development here. And when asked about how the embryos were kept during their earlier development, Lamm said, "We are not sharing much about this at this time."

It's a bit frustrating that more details on this work aren't available. It's nice to know that progress is being made on a very risky project, but one of the better ways to reduce risk is to have other labs validate the things you're doing along the way. Some of this information, such as the DNA segments involved in craniofacial development, would be of general interest to developmental biologists. Hopefully, over time, the company will continue to submit some of its work to peer-reviewed journals.

In the meantime, the clear indications of progress suggest that some of the unique features of the marsupials—relatively rapid generation times, accessible reproductive system, and many similarities to well-studied placental mammals—are helping this project move ahead at a reasonably rapid clip. That's not a guarantee it'll get all the way to something resembling a thylacine. But if it doesn't, then it will at least help us understand why de-extinction doesn't work sooner than work on the mammoth will.

John is Ars Technica's science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.