A complex web of policy, psychology and profit has consumers staring down record-high balances. Five everyday borrowers shared how they got here.

A classically trained French hornist by education, Nick Wolny is a managing editor at CNET, where he oversees CNET Voices as well as coverage related to consumer spending, consumer tech and personal finance. He is also the finance columnist for Out magazine and a frequent television correspondent. Prior to journalism, Nick owned a content marketing agency, a business he converted into a fractional consultancy upon pivoting his career, and has previously written thought leadership columns for Fast Company, Business Insider, Fortune and Entrepreneur magazine. A rural Illinois boy at heart, he's now based in Los Angeles.

Expertise Consumer spending | Consumer tech | Personal finance | Financial independence (FI) movement | LGBTQ+ equity Credentials

- He was named a "40 under 40" by the Houston Business Journal in 2021.

16 min read

As soon as Josué Henriquez turned 18, he applied for a credit card. He wanted to start building his credit so he could one day finance the purchase of a car or home.

"I was told it was the only way I could start my credit in this country," he says, having relocated to the US from El Salvador as a child.

His credit card limit was low at just $500, with a requirement to keep $250 in a savings account at all times. But over the next decade, as more offers rolled in, both his credit limits and balances ratcheted up. Henriquez's credit card bills ballooned to over $25,000, and he eventually sought out a debt settlement company for help.

"I had five credit cards at the time. Now I only have two," he tells me. The rest were shut down as part of his debt management plan, which ravaged his credit report. Now 33, the San Francisco resident eventually got his high-interest debt down to zero by following a four-year payment plan.

Many of us are headed in the opposite direction.

Credit card debt in America continues to break records. After a brief payoff period during COVID-19 lockdown powered mainly by stimulus checks, our collective overall credit card bill became a 13-digit number last year, and now sits at $1.14 trillion according to the most recent Household Debt and Credit report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Center for Microeconomic Data. Consumers typically make larger credit card payments in the first quarter, but both this year and last year the quarter-over-quarter balance remained nearly flat.

What's more alarming is that the cost of carrying this debt has also increased. Credit card APRs went up 30% in an 18-month period to the highest interest rate we've ever seen, rendering monthly payments less productive and eating away at consumers' budgets more than ever before.

Credit card debt is just one type of debt we face in our lifetimes, along with mortgages, car loans, student loans and medical debt. But the credit card is uniquely powerful. Credit cards are comparatively easy to obtain, aggressively marketed and a lasting cornerstone on your credit report, the financial reputation marker that determines your credit score and eligibility to fund future milestone purchases at reasonable interest rates. For decades, credit cards have been a cash cow for banks and retailers alike.

The way we use a credit card reflects the learned behaviors and financial education we've internalized throughout our lives, and advertisers often exploit this sometimes-irrational psychology. Using a credit card has never been easier, as digital wallets now let us make certain purchases with a single click, tap or scan. E-commerce has also accelerated new financing iterations like "buy now, pay later," a credit card döppelganger that gives us yet another way to trick our brains by separating the act of buying from the act of paying. One Harris poll found that 43% of BNPL users were behind on payments and that a third of respondents had over $1,000 in outstanding BNPL loans.

Then there are the vibes. A credit card isn't necessarily bad, especially if you pay off your balance every month, and the perks and points are sexy. But the credit card debt is uncomfortable to talk about; it feels shameful and taboo. "How we got into this mess is the discomfort around confronting what credit card debt is and how to get rid of it," says Nikki Macdonald, a certified financial planner at Northwestern Mutual.

In this article:

- Why we rack up credit card bills to feel better

- Credit card balances have become our emergency funds

- Credit card math is hard to grasp

- Your minimum payment is really profitable for lenders

- You can't opt out of the credit card machine

- How to navigate the credit card debt crunch

Credit can be a helpful tool in hard times, but it can also be quietly destructive. As I spoke with borrowers, financial experts and scholars on the topic, it became clear that behind our fantastic plastic is a powerful system that has become increasingly deregulated and exploitative, making it harder to escape the debt machine.

These are the stories of those systems, the people navigating them and what we can do to better secure our financial future.

Why we rack up credit card bills to feel better

For Carmen Cusido, a 40-year-old public relations professional based in New Jersey, spending was a way to navigate grief.

"My mom died April 28, 2019, and my dad died on August 22, 2020," she tells me. "At that point, I was like, 'Oh my God, I'm completely alone in the world.'" She invested in therapy to support her mental health, and traveled to four new countries. "I would always find deals. I didn't think I was spending that much money," she says.

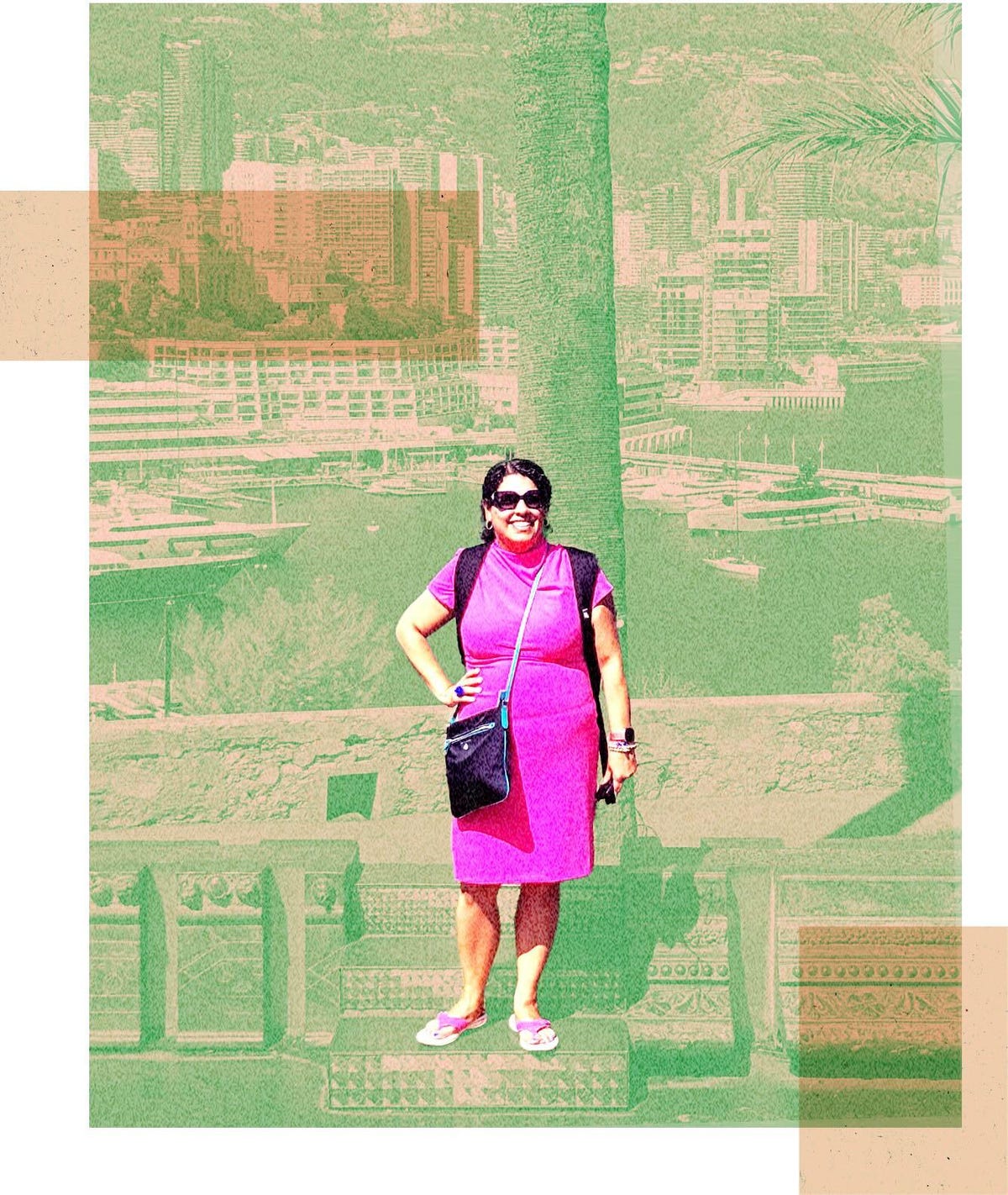

Carmen Cusido

Photo courtesy of Carmen Cusido. Illustration by Zooey Liao/CNETAt the start of 2023, Cusido took out a $13,000 debt consolidation loan to streamline her credit card balances into one monthly payment. But instead of her total debt burden going down, it's gone up.

"I've had a lot of heartbreak," she says. She broke off an engagement last spring and booked a trip to Greece to get away from it all, blowing the budget. Upon reflection, Cusido noted how previous experiences had shaped some of her money behaviors.

"I've had unhealthy relationships in the past. One boyfriend I had early on in life told me my teeth are crooked, so I got braces again. Then a different boyfriend told me my clothes were drab. Now I have two and a half closets' worth of clothes." She says her current goal is to have half her loan debt paid down over the next six months.

The people you care about can leave both positive and negative lasting impressions on you, and how you spend money may be directly tied to the experiences you've had in your relationships, says Traci Williams, a board-certified psychologist and certified financial therapist. "The pain of your experience lingers if it isn't addressed, and spending money is one way you might try to soothe that pain," she tells me.

The psychology of retail therapy

When we're stressed or sad, we want something that will make us feel better. We've come up with a pet name for this fix: retail therapy. There are two psychological feedback loops at work in retail therapy, and both of them are easy to reinforce.

The first is that the mere anticipation of using a credit card for a purchase activates the reward network in our brain, according to a 2021 study published in Scientific Reports. Researchers did brain scans of subjects as they considered buying Xbox controllers. What they found was a strong "step on the gas" correlation; the opportunity to pay with a credit card-powered repayment plan was exciting and anticipatory for the brain, releasing dopamine. In this way, the neurochemistry behind using a credit card is similar to that of amphetamines.

"Overspending can serve as a coping skill. It's an unhealthy coping skill with potentially long-lasting negative consequences, but a way to cope nonetheless," Williams says.

A second feedback loop in retail therapy is the omnipresence of targeted advertising. We buy what we are told will make us happy, healthy, thin and rich. This was not always the case.

By the early 20th century, most Americans had the basic necessities in life, and consumerism became increasingly necessary to prop up capitalism and supply chains. Corporations became more intentional about the long game of shaping the thoughts of the typical consumer through advertising. They swirled together product features with desire, like when cigarettes were marketed to women as a way to remain thin. Today's car commercials are a classic example of these nuanced marketing techniques. People became interested in buying things not only for utility, but also to align with a status or image that was reinforced to them by retailers.

One way this targeted advertising shapes our perception is through sheer repetition. Those damn display ads follow you around for a reason: The more we see something, the more familiar it feels, and humans are drawn to familiarity. In psychology, this is known as the mere-exposure effect.

"It can be helpful to remind yourself that a company's goal is to get you to spend," Williams says.

Carmen Cusido, 40, during a trip to Monaco. She traveled more after her parents died in 2019 and 2020 as a way to navigate grief.

Photo courtesy of Carmen Cusido. Illustration by Zooey Liao/CNETCredit card issuers use these same targeted advertising techniques and were innovators for doing so. As a result, the credit card market matured in the US more rapidly than in other countries, says Josh Lauer, associate professor of communications at the University of New Hampshire and author of the book Creditworthy: A History of Consumer Surveillance and Financial Identity in America.

"An element of sophistication in this credit card industry was producing applicants using credit profiles to make guesses about who should be targeted for a promotion," Lauer tells me.

Retail therapy reinforces behavioral patterns. Credit cards add an extra dopamine hit, and advertisers aim to exploit this brain chemistry however they can.

Credit card balances have become our emergency funds

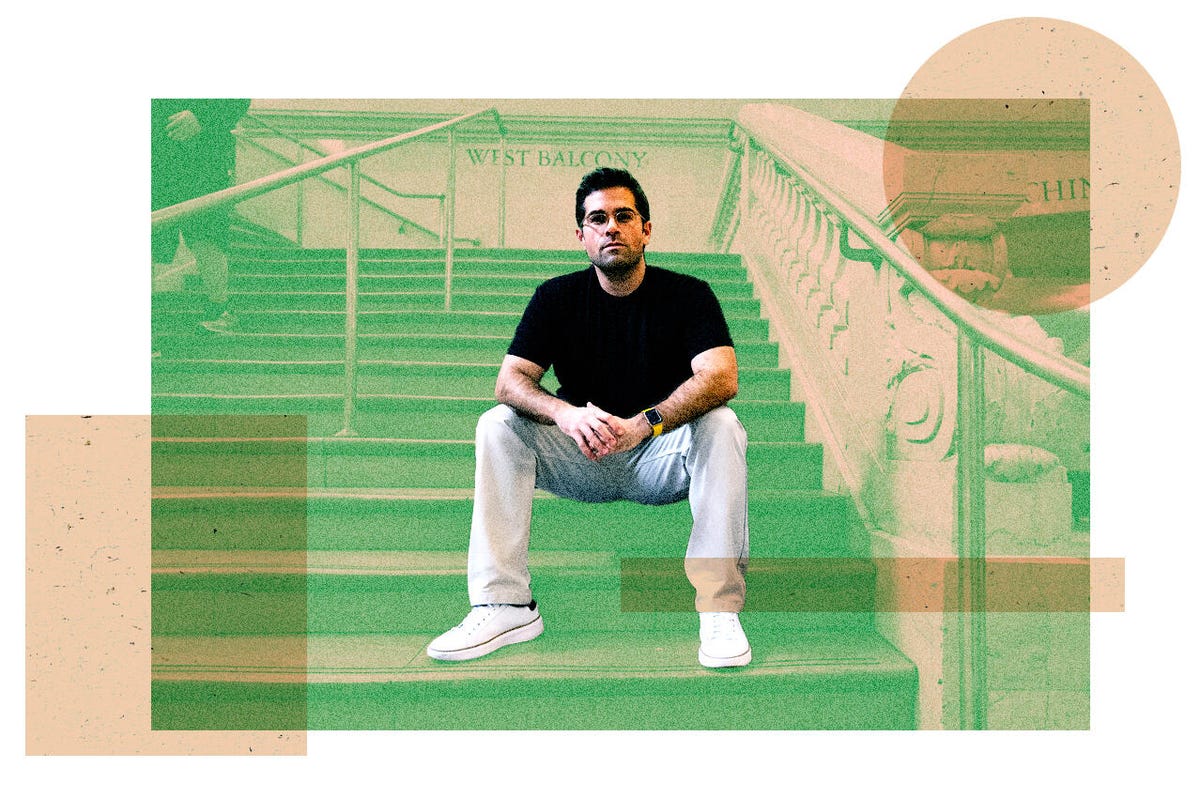

Ian Group

Photo courtesy of Ian Group. Illustration by Zooey Liao/CNETAbout 55% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, 36% have more credit card debt than emergency savings and 22% have no emergency fund at all. Many people lean into credit cards for emergency expenses not because they want to, but because they have to.

When you need extra cash for an emergency and don't have it, credit cards and personal loans are the fastest way to cover unexpected costs. Ian Group, a current personal finance creator and former lawyer, found this out the hard way.

"I figured I would come out of law school, make a lot of money and the loans wouldn't be a big deal," he tells me. Although he graduated at the top of his class, he also had $190,000 in student loans, and could only land a clerkship with a $50,000 salary. This left little wiggle room for emergencies, let alone making full loan payments.

"Things just came up, which I think resonates with a lot of people who are in credit card debt," he says. Since all his monthly income went toward living expenses, setbacks like car troubles were financed with a swipe, and Group soon racked up $20,000 in credit card debt. He also took a forbearance on his student loans during his clerkship, which paused his payments, but interest kept accruing. His student loan debt grew faster, reaching $210,000 at its peak.

"I felt really sick when I saw that," he says. "I should have paid more attention, because those decisions had a big ripple effect on my future."

The inertia of building up an emergency fund

Emergency funds are a challenge for millions because income has stagnated in comparison to both rising worker productivity and the rising cost of goods. From 1979 to 2013, hourly pay for middle-wage workers increased 6% and pay for low-wage workers decreased 5%, whereas pay for very high-wage workers increased 41%, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit think tank.

If we don't have much in savings, we're more likely to lean into credit cards and carry higher-interest balances when budgets are strained. Current credit card provider APRs make this strategy more treacherous.

When inflation hit a 40-year high in 2022, the Federal Reserve stepped in to try to slow down the economy. The central bank raised rates 11 times, driving up the cost of borrowing. Anytime the Fed raises rates, a credit card provider will typically raise interest rates on their credit card products, too. Average APRs have spiked to over 20%, a 30% increase over the last year and a half, with retail card APRs at nearly 29%, and revolving credit card interest is the dominant profit driver for banks and lenders.

For those who choose higher education, an additional financial hurdle looms. From 2000 to 2020, average post-secondary tuition costs outpaced wage growth by 111.4%, according to the Education Data Initiative, and students now borrow an average of $30,000 for a bachelor's degree. Average student loan debt has tripled since 2007. Debt burdens have become so mainstream that some employers are adjusting their benefits packages to allow workers to substitute a student loan payment stipend for their 401(k) match, an alternative that leaves workers perilously behind on saving for retirement.

Ian Group, 38, pictured here in New York City. After he graduated law school with $190,000 in student loans, his initial clerkship salary left no wiggle room to save. When emergencies came up, he paid for them with a credit card, accumulating an additional $20,000 in credit card debt.

Photo courtesy of Ian Group. Illustration by Zooey Liao/CNETGeneration Z, the population segment born between 1996 and 2010, is already feeling the credit card inertia that often comes from having low cash reserves. An FRBNY report found that 1 in 7 Gen Z credit cardholders is already maxed out; this is partially because younger borrowers typically have lower credit limits. The median credit limit for Gen Z borrowers was $4,500, compared to at least $16,000 for older generations.

Today's young people also adopt credit cards more broadly than previous generations did when they were their age. A report from TransUnion found that 84% of 22-to-24-year-olds had a credit card in 2023, compared to just 61% of millennials when they were that age back in 2013, and 75% of Gen Z respondents said the pandemic negatively affected their finances.

Credit card math is hard to grasp

To be clear: Credit cards are a handy financial tool when used judiciously, and benefits like cash-back rewards can actually stretch your budget a bit further. Where we struggle is in fully understanding the impact of making minimum credit card payments.

For Ali and Josh Lupo of upstate New York, not realizing the true cost of minimum payments kept them stuck for years. Formerly both social workers, the couple now run @theFIcouple, a personal finance online education company. The couple says what held them back in their twenties was falling into the minimum payments trap.

"We were accruing more interest than we were actually paying down on the credit card," says Josh, 33. "Month after month, year after year, our credit card debt swelled. We felt stuck."

Similar to Group, the Lupos' credit card debt sat alongside student loan debt, over $100,000 at its peak, all of which the couple eventually paid off. Their next financial challenge has been navigating the exhaustion of first-time parenthood.

"As a new parent, my life is exponentially harder," says Ali, 32, as she passes their infant to her husband during our call. "My spending has gone up, because if there's anything that can make my life a little easier or make me feel better, I'm gonna push the easy button and do it. It is so much more expensive to exist."

Ali and Josh Lupo say paying the minimums on their credit cards kept them "stuck" for years. They eventually adjusted their financial habits, a journey they began documenting on social media in November 2021.

Photo courtesy of Ali Lupo. Illustration by Zooey Liao/CNETAt current credit card APRs, paying only the minimum means you'll pay considerably more than the original balance by the time you're done. The Credit CARD Act of 2009 requires lenders to issue minimum payment warnings in their correspondence, but a financial literacy gap remains.

"I think there's confusion around what a minimum payment does," Macdonald says. "People are like, 'Oh, I always pay my minimums,' as if they're telling me 'No, I'm good.' I'll show you the calculation of how long it's going to take to pay that off — it's not good."

Stacey Black, lead financial educator at not-for-profit credit union BECU, agrees. "This happens to a lot of people," she tells me. Black says it starts with education; she teaches financial literacy classes to high school and college students, and sees firsthand how young people are often tasked with making important money decisions without understanding the fundamentals of debt collection.

"When I was 18, I had no clue. I went to the mall and got a credit card, used it, charged it to the limit, then got another one," Black says. "I did not understand the impact that would have on my financial future." She says that by being open and honest in class about the mistakes she's made, she gets a lot of people to also share their individual stories, although "they'll wait until after class, and then come up to me and say 'this is my situation.'"

Black says that when she asks students who already have a credit card how they got it, they say their parents gave it to them, and that "they have no clue" how to manage it.

Your minimum payment is really profitable for lenders

Credit cards are highly profitable for lenders because APRs and interest rates are hard for us to wrap our heads around. "Most financial costs don't have visible price tags," Morgan Housel writes in his 2020 bestseller The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness.

Banks figured this out in the 1980s. They realized that, to make someone use their credit card more, you simply need to make them feel like they're spending less. Banks lowered the minimum monthly payment on credit cards from 5% to 2% of a borrower's balance. They also increased consumers' overall credit limits, particularly for big spenders.

For borrowers like Josué Henriquez, these increases create temptation, even after paying down his debt consolidation loans. "Because I do payments that are like $2,000 or $3,000 at a time, my credit card company will increase my credit line, which is not helpful because then I spend more," he tells me. "Between my two credit cards, I have a $50,000 credit line, which is a lot of money."

A 2022 analysis from the Federal Reserve found that interest accounted for 80% of total credit card profitability, and credit card borrowers were charged $105 billion in interest that year.

Josué Henriquez, 33, pictured at right while visiting El Salvador. He worked with a debt relief company to consolidate and pay down his $25,000 in credit card debt.

Photo courtesy of Josué Henriquez. Illustration by Zooey Liao/CNETThe desire to pay less in the moment helps other versions of credit like BNPL take flight. "One of the things that we see now with the rise of buy now, pay later is that people just have more individual accounts," says Andrew Housser, co-founder and co-CEO of Achieve, a digital personal finance platform. "We see that on the front end of Achieve Resolution, the business of ours that helps people who've gotten in over their head with debt. We see people with more lines of credit, irrespective of actual dollars." Recent research from Achieve's think tank found that 11% of respondents who were more than 30 days past due on a debt said they were delinquent because they had simply forgotten to pay.

Buy now, pay later leads to statistically higher average purchase amounts, but it continues to surge in popularity, much to the delight of sellers. A blog post from financial technology giant Stripe said businesses that enabled BNPL on their checkout platforms saw a 27% increase in sales volume. And because BNPL data doesn't appear on credit reports, lenders are blind as to how many micro-loans consumers have taken out, as well as whether or not they're keeping up with the payments, an opaqueness that has some lending institutions calling for more stringent regulation.

"Buy Now, Pay Later is engineered to encourage consumers to purchase more and borrow more," reads a September 2022 press release on the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's website.

You can't opt out of the credit card machine

So why not just close out all your credit cards and call it a day? Credit cards wield power over us by shaping our financial identity in the form of the credit score.

The credit score is a three-digit number that determines both your eligibility for and cost to obtain future financing. Before there were digitized credit scores, there were hundreds of credit bureaus. Early versions of these bureaus were deeply flawed in their subjectivity, often documenting borrowers as less creditworthy because of their gender, race and other factors. Eventually, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 were passed. The legacy of historical credit structures still contributes to present-day inequity through both wealth and wage gaps.

Credit bureaus eventually consolidated down to a few major players, which together retained the tech firm Fair, Isaac and Company to develop a proprietary industry algorithm: the FICO score. FICO reached household name status when it was adopted in 1995 by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-adjacent agencies that work with lenders to manage a majority of mortgage loans in the US. Translation: Once the FICO score determined what kind of house you could buy, people began caring about their credit scores and financial reputations a whole lot more.

How do you get that credit score up? By taking on and using credit, of course. Credit history is a major consideration in a borrower's overall credit score, accounting for 35% of the FICO pie. For most Americans, the most accessible debt instrument for building up this credit history is — say it with me — a credit card.

Without other debts in the picture to build up your history, opting out of the credit card game is also a risk. You'll end up having no credit score, making you "credit invisible," a scenario that applies to an estimated 26 million Americans and can strangle your ability to both obtain financing and build generational wealth.

How to navigate the credit card debt crunch

Between corporate profit drivers and our well-ingrained spending habits, it can feel impossible to dig yourself out of the credit card debt abyss. Revisiting the fundamentals of personal finance can help.

"We really bring it back to basics when we talk to our clients," Macdonald says. "It all comes down to having a budget and really understanding what the priorities are, along with how we create dollars to tackle each priority or bucket." If you need outside help, consider researching credit counseling organizations; these are nonprofits that can advise you on debt management, whereas debt settlement and debt consolidation companies are typically for-profit, according to the CFPB.

Also consider examining your thought patterns around money to cultivate awareness and behavior change. Beneath the numbers, much of financial planning is about psychology. This includes how your brain works, the ways you think about money and what your parents did or didn't teach you growing up.

"Working through your emotionally painful past, developing a positive sense of self and creating healthier coping skills can reduce your reliance on emotional spending," Williams says.

Last, take a good look at whether you have enough money to actually make progress on your personal finance goals. Households may need to transfer balances or find an additional stream of income to bring in more money. Once you're in surplus, choose a debt payoff method; the avalanche method prioritizes paying down your highest-interest debt first, whereas the snowball method prioritizes paying down the lowest balance first to build mental momentum.

Henriquez's time living debt-free was short. He's back to being $20,000 in credit card debt, and is working on bringing that down.

"Four months ago, it was a lot more," he tells me. "I was between jobs. I pretty much had both cards maxed out. I feel like that's what this country has become."

As wages sputter and credit card balances soar, financial professionals worry that we're digging ourselves too deep. Credit card debt is nuanced, a sprawling issue with many factors at play, and the way out depends on your unique circumstances. Personal finance is personal.

By giving ourselves the gift of financial literacy, as well as understanding the psychology-powered advertising machinery that exists all around us, we can change our current situation and cultivate a better future.

Visual Designer | Zooey Liao

Video | Jesse Orrall, Chris Pavey

Motion Graphics | Viva Tung

Senior Project Manager | Danielle Ramirez

Director of Content | Jonathan Skillings

Editor | Laura Michelle Davis